Beneath the surface of your skin, intertwined with powerful muscles and sturdy bones, lies a critical yet often overlooked network of fibrous tissue that is fundamental to your every movement: the aponeurosis. While tendons often steal the spotlight in discussions about musculoskeletal health, aponeuroses play an equally vital, if not more extensive, role in the biomechanics of the human body. Imagine a vast, incredibly strong sheet of connective tissue that acts as both an anchor and a spring, facilitating force transmission, providing structural integrity, and absorbing the immense stresses of physical activity. This is the essence of an aponeurosis. Understanding this structure is not just an academic exercise; it is key to comprehending common sources of pain, such as the debilitating heel discomfort of plantar fasciitis, the strain in an athlete’s abdomen, or the tension across the lower back. This article will delve deep into the world of aponeuroses, exploring their unique structure, critical functions, and the significant consequences that arise when they are injured or compromised, ultimately revealing why this “silent scaffolding” is indispensable for your mobility and strength.

What Exactly is an Aponeurosis? Defining the Structure

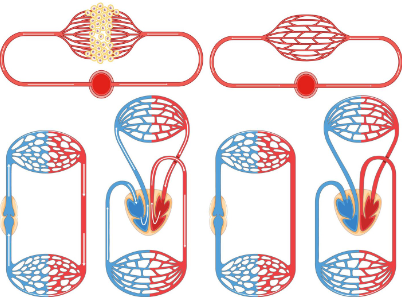

An aponeurosis is a flat, broad, sheet-like tendon primarily composed of densely packed, parallel collagen fibers. This composition is similar to that of a regular tendon, which is why the two are often mentioned in the same breath. However, the key distinction lies in their shape and, consequently, their function. Where a typical tendon is a narrow, cord-like structure that connects muscle to bone, an aponeurosis serves as a expansive sheath or ribbon that performs a wider variety of roles. It can attach a muscle to the part of the bone that needs a broad area of attachment, or, more importantly, it can serve as a connective sheet between two muscles, allowing them to function as a cohesive unit. The collagen fibers within an aponeurosis are arranged to withstand tremendous forces from multiple directions, providing not just strength but also a degree of flexibility. This combination of resilience and slight pliability allows the aponeurosis to act as a dynamic component of the musculoskeletal system, storing and releasing elastic energy much like a spring, which is crucial for efficient locomotion and powerful movements like running and jumping.

The Critical Functions: More Than Just a Simple Attachment

The aponeurosis is far from a passive structure; it is a dynamic and multifunctional component of our anatomy. Its primary role is the efficient transmission of force generated by muscle contractions. When a muscle like the latissimus dorsi in your back contracts, it doesn’t just pull on a single point; it pulls on a broad aponeurosis that distributes that force across a wider area of the bone or onto other muscles, leading to smoother and more stable movement. This distribution is essential for preventing stress concentrations at a single point, which could lead to avulsion fractures or other injuries. Furthermore, due to their elastic properties, aponeuroses function as energy-saving mechanisms. During the weight-bearing phase of a stride, the plantar aponeurosis in the foot stretches, storing kinetic energy. This stored energy is then released as the foot pushes off the ground, propelling you forward with less muscular effort required. This spring-like action is a fundamental principle of efficient bipedal movement. Additionally, aponeuroses serve as protective sheaths, covering and separating muscles to reduce friction, and as structural components that help maintain the shape and positional integrity of the abdomen and other regions.

Aponeurosis vs. Tendon: A Clear-Cut Distinction

While both are composed of collagen and serve to connect muscle to something else, the difference between an aponeurosis and a tendon is a matter of form and function. The most apparent difference is their physical shape. A tendon is a tough, flexible, and rope-like structure, while an aponeurosis is a flat, sheet-like membrane. This fundamental difference in morphology dictates their specific roles. A tendon is designed for focused, high-tension pull in a single direction, channeling the entire force of a muscle to a specific bony prominence to create joint movement, like the Achilles tendon pulling on the heel bone to enable plantarflexion. An aponeurosis, in contrast, is engineered to distribute force over a broad area. It is the difference between pushing a thumbtack with your finger (tendon—focused force) and pressing a book with your open palm (aponeurosis—distributed force). This distribution makes aponeuroses ideal for anchoring large, flat muscles like those of the abdomen (the rectus abdominis is enveloped by the aponeuroses of the oblique muscles) or for creating the broad, stable attachments needed for the muscles of the skull (the galea aponeurotica).

When Things Go Wrong: Common Aponeurosis Injuries and Conditions

Given their constant involvement in movement and load-bearing, aponeuroses are susceptible to injury, typically through overuse, acute trauma, or degenerative processes. The most well-known condition involving an aponeurosis is Plantar Fasciitis. The plantar fascia is a thick band of tissue—an aponeurosis—that runs along the bottom of the foot, connecting the heel bone to the toes. Repetitive strain can cause micro-tears and inflammation in this structure, leading to the characteristic stabbing heel pain, especially with the first steps in the morning. Another common issue is Achilles Tendinopathy, and while the Achilles is technically a tendon, it is formed by the convergence of the aponeuroses of the gastrocnemius and soleus muscles in the calf; thus, problems often originate in these aponeurotic tissues. In the hand, Dupuytren’s Contracture is a disease that specifically affects the palmar aponeurosis, causing it to thicken and tighten, which slowly pulls one or more fingers into a bent position. Furthermore, strains and tears can occur in the abdominal aponeuroses, often referred to as a “torn fascia,” which can be a debilitating injury for athletes. These conditions highlight the aponeurosis’s vulnerability and its critical importance to normal, pain-free function.

Conclusion: The Unsung Hero of Your Musculoskeletal System

The aponeurosis is truly an unsung hero within our bodies. It operates silently and efficiently, providing the essential structural framework that allows our muscular and skeletal systems to work in harmonious concert. From distributing the immense forces generated by our powerful muscles to storing and releasing the elastic energy that makes our movement efficient, the roles of the aponeurosis are both foundational and dynamic. Understanding this vital tissue provides a deeper appreciation for the complexity of human anatomy and sheds light on the root causes of many common musculoskeletal ailments. By recognizing the importance of these broad, sheet-like tendons, we can better appreciate the need for targeted strengthening, gradual conditioning, and proper care to maintain their health, ensuring that this silent scaffolding continues to support a lifetime of movement.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ)

Q1: Is an aponeurosis the same as a fascia?

While both are types of connective tissue, they are not identical. Fascia is a more general term for the web-like, three-dimensional network of connective tissue that surrounds and penetrates every muscle, bone, nerve, and organ in the body. An aponeurosis is a specific type of fascia that is characterized by its dense, regular, sheet-like structure designed specifically for force transmission. Think of fascia as the entire “fabric” and an aponeurosis as a specific, reinforced “seam” within that fabric.

Q2: Can a damaged aponeurosis heal on its own?

Yes, aponeuroses can heal, but the process is often slow due to their relatively poor blood supply compared to muscle tissue. The healing process involves the formation of scar tissue, which is not as strong or elastic as the original collagen structure. Recovery typically requires rest, controlled loading through physical therapy, and sometimes medical interventions like shockwave therapy or surgery for severe tears. Proper rehabilitation is crucial to restore strength and flexibility.

Q3: What is the most common aponeurosis injury?

The most common and well-known injury is Plantar Fasciitis, which affects the plantar aponeurosis in the foot. It is an extremely prevalent cause of heel pain, especially among runners, people who are on their feet for long periods, and those with specific footwear or biomechanical issues.

Q4: How can I strengthen my aponeuroses to prevent injury?

You cannot directly “strengthen” an aponeurosis like you would a muscle through weightlifting. Instead, you build its resilience and tolerance to load indirectly. This is achieved through consistent, progressive exercise that stresses the tissue in a controlled manner, such as calf raises for the plantar and Achilles aponeuroses or core stabilization exercises for the abdominal aponeuroses. Eccentric exercises (loading a muscle as it lengthens) are particularly effective for promoting tendon and aponeurosis health.

Q5: Are there any specific risk factors for aponeurosis injuries?

Yes, several factors can increase risk, including:

-

Overuse: A sudden increase in activity intensity or duration.

-

Age: Tissues lose elasticity and become more prone to degeneration with age.

-

Biomechanics: Flat feet, high arches, or an abnormal walking gait.

-

Obesity: Excess weight puts additional strain on load-bearing aponeuroses like the plantar fascia.

-

Occupations: Jobs that require long hours on your feet or repetitive motions.

-

Diabetes: Is linked to a higher incidence of conditions like Dupuytren’s contracture.